The Real Reason Feedback Feels Unsafe at Work

Your company says it values “open feedback.” It appears in trainings and in the company values. Leaders ask for candor in town halls. Teams are encouraged to speak up early and often.

So when a process starts breaking, you do what a responsible manager would do. You share a clear observation. You name the impact. You suggest a workable alternative.

Nothing dramatic happens in the moment. People nod. Someone says, “Appreciate you raising this.”

Then, a few weeks later, you feel the shift. You stop getting pulled into early meetings. A partner who used to respond quickly goes quiet. In a casual conversation, someone jokes that you are “always pushing back.” In your next check-in, your manager says your “approach can land strong” but cannot explain what to do differently.

The message wasn’t wrong. The environment just wasn’t built to handle it.

Many managers are not hesitating because they lack courage. They are responding to systems that quietly reward compliance and discourage friction. Even measured, respectful feedback can carry unpredictable consequences.

If one kind of hesitation is internal, this one is external. It comes from watching what happens when people speak plainly.

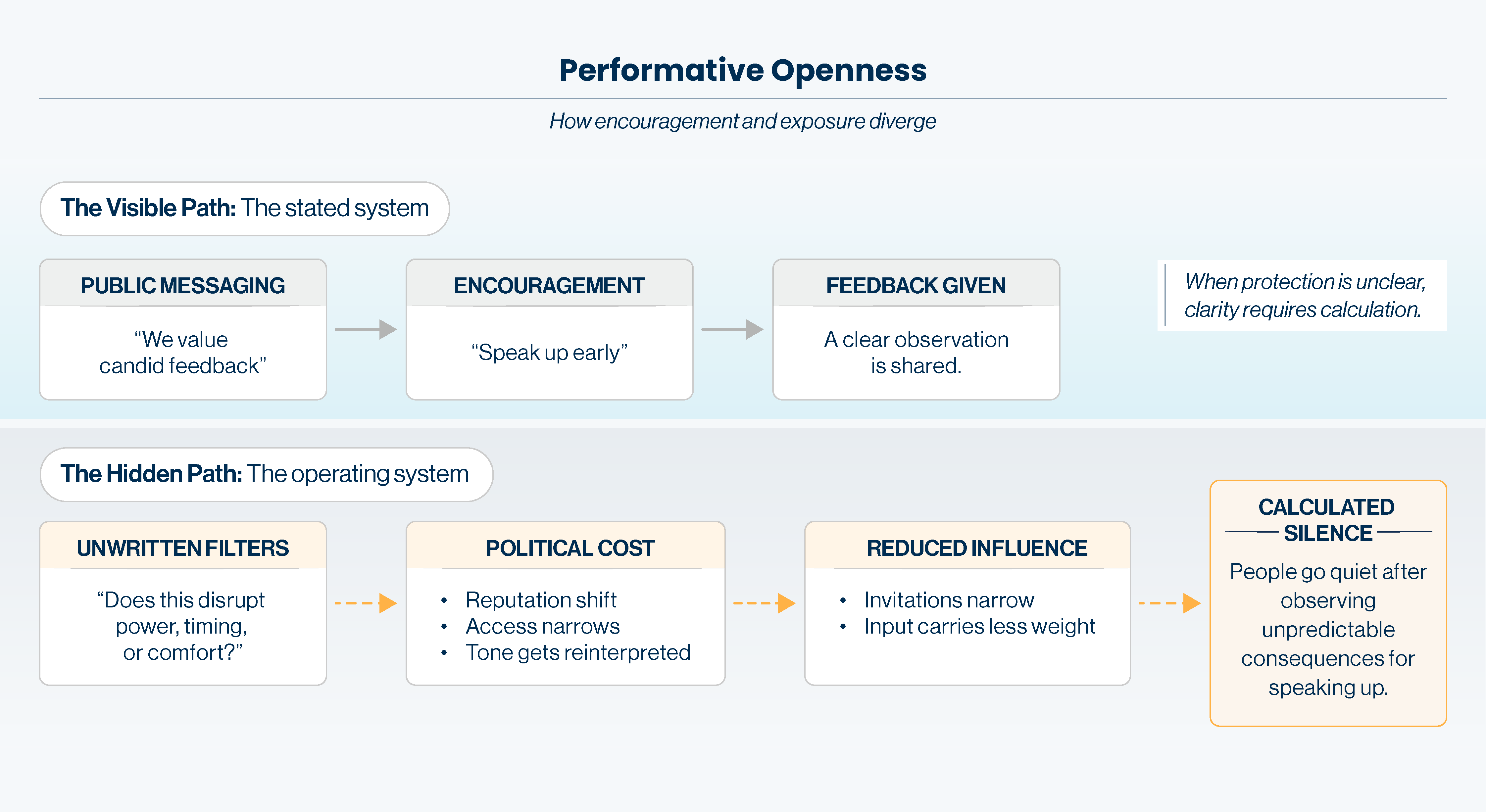

Performative openness

Performative openness is when an organization praises feedback in principle but resists it in practice. It is not about one difficult leader. It is a mismatch between what is said and what is protected.

Common signals include:

- Feedback is welcomed after decisions are final. Input is requested when it cannot change the outcome, then cited as proof of inclusion.

- “Safe space” language exists without guardrails. People are encouraged to speak, but there is no clear protection when the feedback is inconvenient.

- Managers carry the risk alone. If you raise a real concern, you absorb the relationship strain, the reputation shift, and the political cost.

Within that pattern, hesitation is not a character flaw. It is pattern recognition. This is why “just be more direct” often feels incomplete. When consequences are unclear, even a skilled communicator has to calculate exposure.

When the context, not the communication, is the problem

When feedback feels unsafe, coaching usually focuses on delivery. Tone. Framing. Curiosity. “Use more questions.” Those skills matter in a healthy environment. They do not repair a misaligned one. Feedback safety is less about tone and more about power, consistency, and what happens after the conversation.

Risk increases when:

- Standards are inconsistent. One person is praised for challenging a decision; another is labeled difficult for the same behavior.

- Consequences are unpredictable. Speaking up sometimes leads to influence and sometimes to exclusion. People cannot tell which outcome they are stepping into.

- Escalation paths are unclear. When the concern involves someone senior, who protects the person raising it? What happens next?

In those conditions, silence is typically self-preservation. A manager is not choosing comfort. They are choosing stability for themselves and their team. That is the real reason feedback feels unsafe at work. The system makes the risk hard to calculate.

Where systems quietly erode clarity

If you lead people, support managers, or design manager training, it helps to name the structural fault lines.

Here are four common ones.

1. Annual reviews tied tightly to compensation

When developmental feedback is directly linked to pay and promotion, every coaching note carries more weight than it should.

People stop hearing development. They hear a case being built. Managers soften language to avoid creating future “evidence.” Employees learn to read between the lines.

The result is vague messaging, late surprises, and distrust. Not because managers are unwilling to be honest, but because the system turns routine feedback into a financial event.

2. “Two-way feedback” without protection

Many organizations say feedback flows in every direction. In practice, upward feedback can carry informal penalties.

A manager raises a measured concern about shifting priorities. A month later, they are described as “not aligned” or “hard to work with.” Nothing overt happens. But access changes. Invitations narrow. Influence shifts.

Without consistent protection, people keep the real feedback private and the public version agreeable.

3. HR positioned as cleanup, not design

In many companies, HR becomes involved only after something has escalated.

That is a difficult position. It often means managing fallouts rather than shaping clear standards, shared expectations, and defined escalation paths before problems arise.

Managers learn that raising issues creates exposure, not resolution. So they handle concerns quietly, or not at all.

4. Values language without process

A company can say “candor” and “trust” all day. If there is no shared process for handling disagreement, values become branding.

People notice what gets rewarded. They also notice what gets discouraged, even subtly. If the real rule is “do not make leadership uncomfortable,” the environment teaches that lesson quickly.

None of this requires bad intent. It only requires a mismatch between messaging and protection.

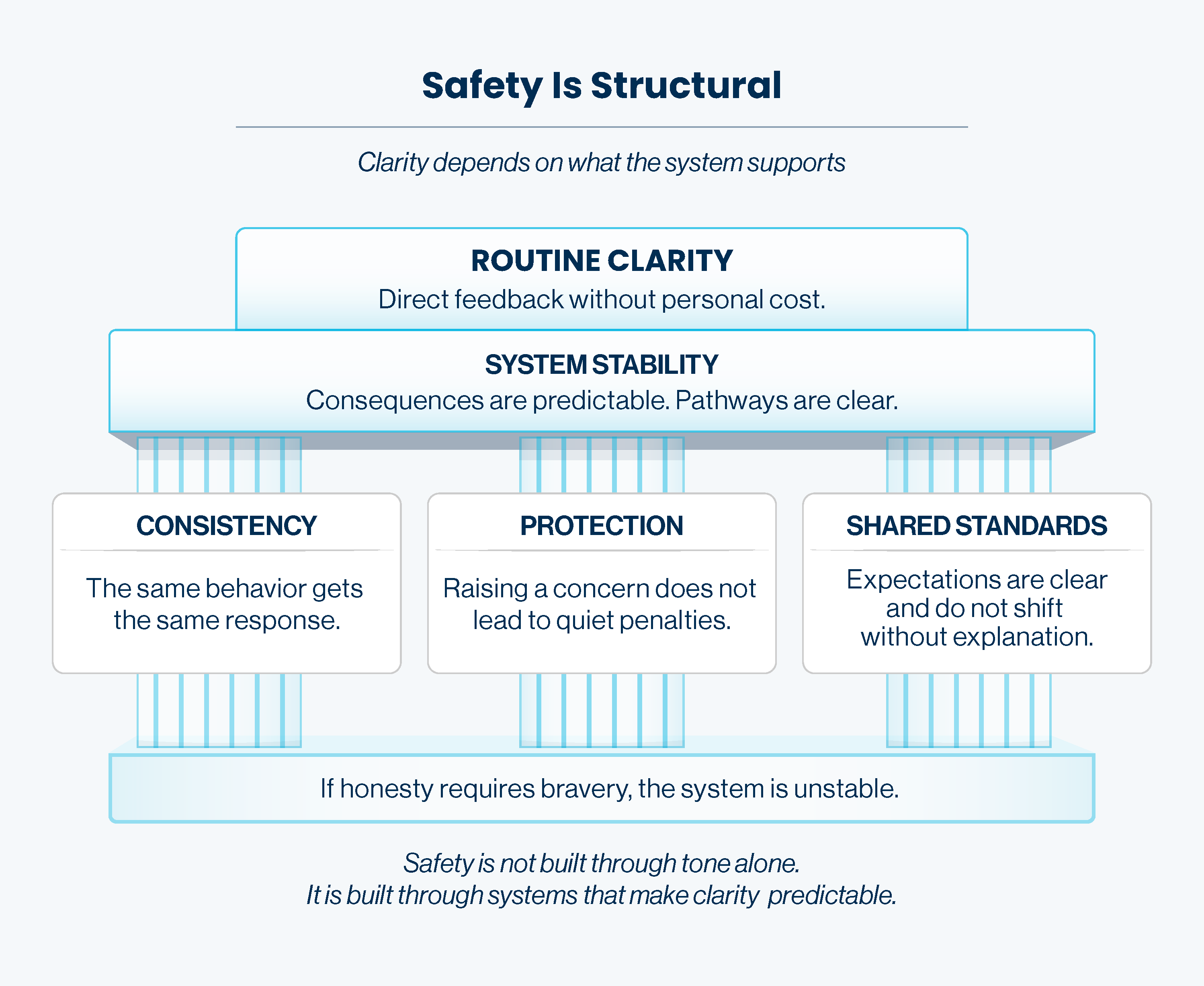

Safety is structural

Psychological safety is regularly framed as a mindset. Be open. Be curious. Be kind. That framing is incomplete.

Safety is structural. It is built through consistent standards, predictable consequences, and clear pathways for raising concerns.

Clarity depends on three conditions:

- Consistency: Similar behaviors receive similar responses across people and teams.

- Protection: Raising a concern does not lead to informal punishment.

- Shared standards: Expectations are explicit and do not shift without explanation.

Here is the truth behind much hesitation: if honesty depends on bravery, the system is already unstable.

Bravery should be reserved for extraordinary moments. Routine clarity should not require personal risk.

When routine clarity becomes risky, managers start managing exposure instead of performance. They choose words carefully. They shrink feedback. They protect their teams by limiting visibility rather than improving the system. That is not weak leadership. It is a rational response to unstable conditions.

A practical anchor: The Clarity Test

This will not fix a flawed system. It will help you read it more accurately.

Ask yourself three questions:

- Is feedback punished later, even subtly?

Not dramatically. In access, assignments, responsiveness, visibility, or how someone is described. - Do expectations change without explanation?

Are people judged by standards that were never clearly named or that shift depending on who is involved? - Are managers carrying risk alone?

If a manager raises a real issue, is there a consistent process that supports them, or is it handled quietly and informally?

If you answer yes to even one, your hesitation is not weakness. It is information.

If you answer yes to two or three, hesitation may be protective.

This is the permission many capable managers need: you can care about clarity, deliver feedback respectfully, and still operate in a context where speaking plainly carries a cost. Naming that is not cynicism. It is accuracy.

If feedback feels unsafe at work, it is worth asking why before pushing harder.

That question matters for managers being told to “have more backbone.” It matters for HR and L&D leaders trying to build a culture of candor. It matters for senior leaders surprised by silence in meetings.

In environments where consequences are inconsistent and protection is unclear, the absence of feedback is not proof that everything is fine.

It is often proof that people are paying attention.

Good managers do not avoid clarity. They notice when the system makes it expensive.